Deflection Defined

To comprehend the process of “crowning” in metal fabrication, one must first understand the concept of “deflection.” Deflection is an engineering term used to describe the amount of deformation or displacement that occurs in a structural element when it is put under a load.

A simple illustration would be to picture a man who decides to get up to clean the rain gutters on his house by running a stiff board across the tops of two step ladders on which he can stand. No matter how thick and hard the board, the closer the man approaches the center, the more it sags and deforms under his weight. (Also, the longer the board, the more it will sag.)

Fabrication equipment such as press brakes and plate rolls can likewise flex or deform slightly in the middle of the ram or roll, where the tool is less supported than at the ends. Even though the machine is applying pressure to form the part, the part is likewise putting pressure back into the machine, which becomes greater towards the center. This temporary deflection of the tooling while under pressure can be transferred permanently into the bend or roll of the finished workpiece.

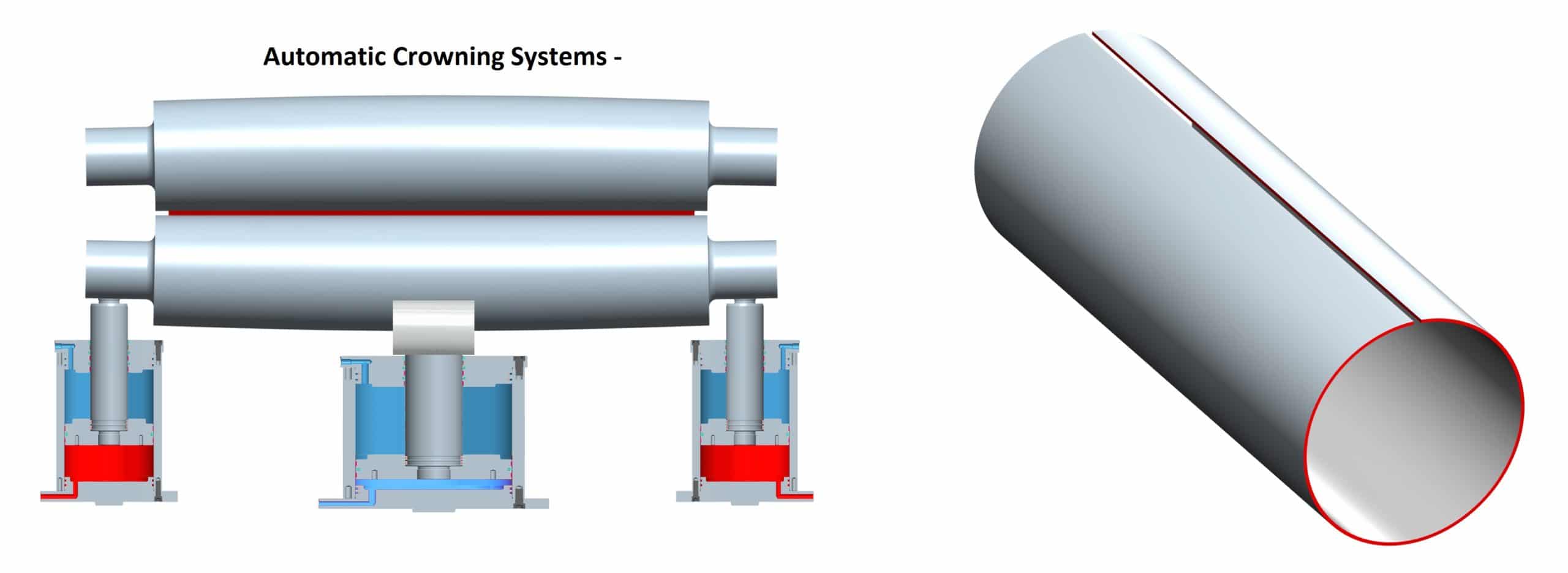

In the case of a plate roll, a “barrel effect” in the rolled part is the likely outcome, where the workpiece has a larger diameter in the middle than at the ends. (Note that overcompensating for deflection can cause another type of deformation, an “hourglass effect” in the finished part where the material is drawn tighter together in the center than the ends.)

Deflection occurs in fabricating machines like brakes and plate rolls because they can’t apply equal tonnage across the length of workpieces. To adjust for this, the process of crowning was developed, which traditionally involves raising the middle of the ram or roll to create a high point (or crown) in order to compensate for the diminished tonnage in the center.

How Is Crowning Applied in Plate Rolls?

If a plate roll doesn’t have proper crowning, it may be impossible to achieve rolled parts that are perfectly parallel along their length. Even if a roll has the correct crowning compensation applied for one thickness of one metal, most metal fabricators will require their plate roll to work with multiple materials in different thicknesses. Each material will affect the machine’s rolls and performance in different ways, so a quality plate roll will be manufactured with optimal crowning built in to allow it to accommodate a variety of different parts.

Optimal crowning is created by using a CNC lathe to grind a top roll into a slight barrel shape that is raised more in the center than at the ends. A formula is programmed into the lathe control that will create the right shape in the roll to equalize pressure when the rolls are brought together with the workpiece between them.

With all other factors being equal, optimal crowning is typically set at 75% of the nominal capacity of a plate roll. For example, let’s say a customer purchases an optimally crowned plate roll with a one-inch thick nominal rolling capacity. That machine should, under the correct pressure, be able to form a cylinder out of three-quarter-inch thick material that keeps all surfaces parallel to each other—in other words, the cylinder has the same diameter along its whole length.

However, different thicknesses of material might require this same machine to be adjusted in order to correctly roll them. Since a certain amount of pressure has to be applied to deflect the crowning out of the rolls at the thicker end of the machine’s range, a thinner plate like quarter inch might yield long before that pressure is reached. Not being able to deflect the optimal crowning will distort the plate and result in an hourglass-shaped part—a part tighter in the middle than at the ends.

The range of a roll (in thickness, width and diameter) really depends on the tolerance—with accepted variance—of the customer’s parts. Specific crowning can be applied to any machine to reach the desired range of material characteristics and part tolerances. Options can be installed on the machine to adjust for different tolerances, such as dynamic crowning on the bottom rolls or an over-the-top roll deflection compensation system.

In most cases, a plate roll should be ordered with the correct crowning applied to the top roll that accommodates the customer’s most common material. Then adjustments can usually be made to work with other materials.

How to Compensate for Crowning Deformations

Two common methods for compensating for incorrect crowning are adjusting the pinch pressure to change the parallelism of the roll contact surfaces and shimming with cardboard, wood or metal to add temporary thickness to different sections of the rolls.

If a rolled part is outside of tolerance because of too little crowning compensation—creating a barrel crowning deformation—some possible solutions include:

- Acquire a top roll with greater crowning

- Reduce pinch pressure of the rolls

- Add shims in the middle to offset too much deflection

- Increase initial crowning in the center of the rolls

- Slow down the rolling speed

- Install an overhead support to help limit roll deflection

Also, if the part falls outside of the roll’s capacity range because of being too thick or too heavy, additional passes in the machine can help offset the deformation—as long as the material does not harden during the multiple passes.

If a rolled part is outside of tolerance because of too much crowning compensation—creating an hourglass deformation—some possible solutions include:

- Acquire a top roll with less crowning

- Increase pinch pressure (although some soft materials may not be good candidates for this approach because of possible damage)

- Shim outer surfaces of the roll

- Reduce initial crowning in the center of rolls

- Roll the part in fewer passes

- Apply more dynamic crowning pressure (if that option is available on the machine)

If a dynamic roll crowning system is added to a plate roll, hydraulic crowning cylinders are installed that can apply variable amounts of force to the rollers from the bottom to eliminate deflection.

Fabricators can also equip their plate roll machines with oversized rolls, which will typically have very limited crowning machined into them. Oversized rolls don’t flex as much as smaller ones and usually won’t yield before the material does, meaning there is little or no roll deflection that needs compensation. The drawback is that as the top roll gets bigger, it may not allow tighter diameters to be rolled.

If necessary, machines can also be ordered with additional interchangeable top rolls with different crowning. High capacity shops may want to eventually consider acquiring multiple machines to readily work with different thicknesses and diameters, so the need to repeatedly make costly, time-consuming adjustments for each job is diminished.

Fabricators should look at adding optimal crowning to any new plate rolls that they purchase, and they should be well-versed in compensation techniques in order to produce quality, uniform parts time after time.